There’s a line Taylor Swift sings to a bully in “Mean” that most of us should tell our mental health demons: “You don’t know what you don’t know.” We might not officially be afflicted with some acronym or spectrum, but we’re a far cry from perfect.

That brings us to “We Can Do Hard Things,” a self-help book that’s sort of a tapas platter of approaches, 20 questions that cover topics from sex and parenting to anger and forgiveness, from losing ourselves to finding happiness. The advice comes not only from authors Glennon Doyle, Abby Wambach and Amanda Doyle (who also have a popular podcast), but from 118 “wayfinders” who chime in with experiences and suggestions.

Here’s a good interview with two of the authors, and you can see all three in this clip from “The Daily Show.”

Glennon Doyle mentions in the interview that she often pursued what she thought was the safe path in her life, but some powerful lessons come from noticing your own challenges. One bit of enlightenment came from this scene in “The White Lotus.”

“I don’t need religion or god to give my life meaning,” Laurie tells her two longtime friends, “because time gives it meaning. We started this life together. We’re going through it apart, but we’re still together and I look at you guys and it feels meaningful. I can’t explain it, but even when we’re just sitting around the pool talking about whatever inane shit, it still feels very fucking deep.

“I’m glad you have a beautiful face, and I’m glad that you have a beautiful life, and I’m just happy to be at the table.”

“I just could cry talking about it,” Doyle said, “because I just felt like, ‘Oh, that’s enlightenment. I’m not grasping at what you have. I’m also not pretending that it doesn’t drive me batshit crazy — AND I’m just grateful to be at the table, regardless of whether I’m the best one or the most beautiful one or the smartest one.’”

The book has all sorts of potential sources of enlightenment. Maybe this from singer Alanis Morissette will do it for you: “The best thing about drugs, alcohol, shopping, work addiction, love addiction is that it feels really, really good for the first twenty minutes. But then it kills you dead. Those twenty minutes were such relief that I didn’t care about dying — until I became a parent. And then I was like: Oh, I have to stick around. I’d like to live to 127 now, whereas in the past I didn’t even care. I would drink tequila so that I could be another temperament. And I miss her sometimes. I think: She was fun. But we’ll find other ways to be fun. The definition of fun changes as we change anyway.”

One key element early in the book describes how often people can be cast in familial roles growing up — hero, scapegoat, peacemaker — that weigh them down as adults.

“We can heal from the roles we played, but I think it starts with grieving,” Amanda Doyle writes. “If you were the scapegoat and you were outcast and vilified by your family; if you were the one who could never be a kid because you were mediating between people; if you were the invisible one who was never seen and so you think you’re not worthy of being seen; if you had to take care of your family by making everyone laugh even when someone else should have been taking care of you; if you were told you were broken when really your family was broken — there’s a lot to grieve there. It’s sad.

“But it’s also liberating to know that family roles are a scam, because it means you can put down your script.”

And, of course, the script turns for parents as their children get older. Or at least it should.

“For me, the hardest part about these children growing up is that they now start to have private lives, not only interior lives but private lives with their friendships and their new partners and their new communities that they’re forging for themselves,” Wambach writes. “That feels hard because it leaves us out and that’s uncomfortable. We have to trust and believe that we did the very best that we could and let them go. I feel confident that they’ll come back eventually — if only to file their grievances.”

“It truly is the most heartbreaking paradox of life that, if you are lucky, your children will not need you,” Amanda Doyle adds, “but what you want most in the world is for them to need you. And tragically, it seems as if the surefire way to ensure your kids won’t want you is for you to need them.”

My two cents: Don’t discard the experiences you had — or your children had — growing up that made you angry or resentful. Use them as motivation.

“Resentment and anger are your best friends,” says Wayfinder Martha Beck, a life coach, “because they sharply point you to the places where your freedom is most constrained.” Steph Curry isn’t known for his anger, but I think he would applaud the sentiment.

Pride and petulance

After the Warriors won the NBA title, you could see all the usual championship merchandise, but one big fan site had a T-shirt that reached right into the soul of MVP Steph Curry. Here it is:

As long as we’re rehashing my old crap, Glennon Doyle often mentions the importance of friendship horseshoes, which I wrote a whole column about several years ago — swiping the idea from her, of course.

Let’s close by stealing three more tapas:

From death doula Alua Arthur: “Often, when making decisions, I try to put myself on my deathbed and consider whether I’ll be happy I did it, sad I didn’t do it, or whether it will even matter. I say, ‘This thing that I’m doing, how important is it going to be to me on my deathbed?’ I futurecast my way to the end. It helps for a lot of things — like a breakup, for example. On my deathbed, will I be happy we broke up? Will I be sad I didn’t do it? Or will it not even matter? If any of those are the case, go ahead and break up, girl.”

From Dan Levy of “Schitt’s Creek” fame: “Oftentimes grief can feel like this incredibly isolated experience. It’s hitting you, and you leave your house, and you look around, and people are in the grocery store, and kids are laughing, and people are carrying on, and you are in grief. You’re in pain. It’s inescapable, insufferable, all-consuming pain. And when people around you are not experiencing that, it can send you into an even greater state of isolation because you think no one understands. But everybody is grieving something. Everybody in the room that you’re in is grieving something. Everybody in the grocery store you’re shopping at is grieving something, if you were to scratch the surface of their lives. And there’s community in that if we can just be more open about it.”

From Glennon Doyle: “There are certain voices inside my head that will never quiet down until they first feel fully heard, acknowledged, and understood. I find myself wondering: What is this part’s problem? Why on earth is it telling me not to eat? Why? Why? Why? Turn it down, turn it down, turn it down. No. Turn it all the way up. It needs to be heard. It’s saying: Glennon, your house wasn’t a safe place to indulge your appetite. So I protected you by keeping us small and safe. That’s what I’m still trying to do. I’m trying to keep you small and safe so we can survive. I’m just trying to protect you. We have these parts that have worked so hard for so long and have done a really good job helping us survive. They just have old information. They just don’t know that we’re safe now and all the rules are different. They just need an update.”

Murphy Slaw

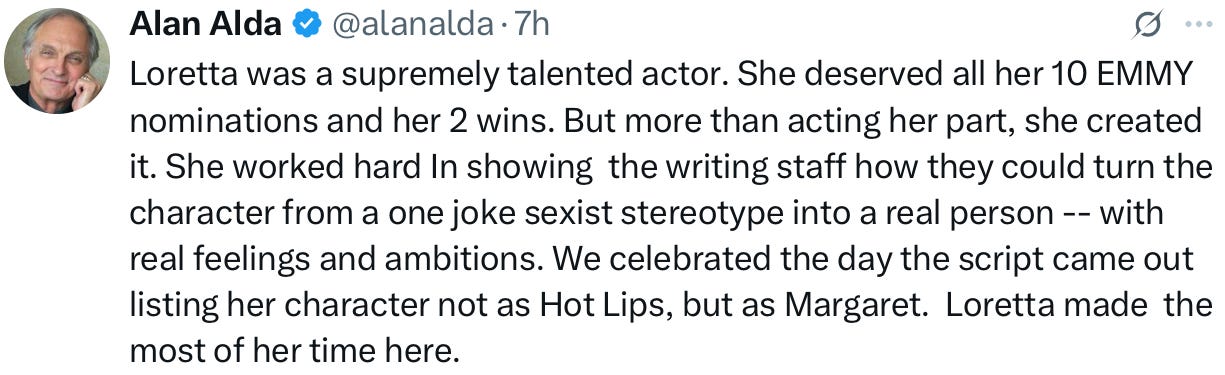

Something old: This tweet from Alan Alda captures how television and pop culture evolved in the 1970s and 1980s, thanks to actresses like Mary Tyler Moore and Loretta Swit, whose genius ensured that their characters wouldn’t be one dimensional. If you were too young to appreciate the talent of Swit, who died last week at age 87, take a minute and take in this video.

Something new: Artificial intelligence is one of the most divisive workplace issues, as this article explains. I have a feeling that absolutists on both sides will spend the next five years screaming at the top of their lungs, then some common sense compromises will be reached.

Here’s why: Artificial intelligence is stupid right now, but it’s getting smarter. And it will wipe out jobs, just as technology has for decades, but it will also strip away a lot of mundane crap and let brilliant people be more brilliant, just as technology has for decades.

One example from a writer: If I wrote a novel, I would cringe at AI reading it aloud, worried about how tone deaf it would sound. But if I wrote a textbook and AI gave students the option of hearing it, it might make the book more accessible to them and more lucrative to me. It’s at least worth exploring with an open mind.

Something borrowed: Sometimes simply being human can lead to a brilliance all its own. Author John Green has spoken about his struggles with obsessive-compulsive disorder, even basing his 2017 novel “Turtles All the Way Down” on a high-school girl with OCD.

The movie version came out last year and is now streaming on Max. It’s well worth a look, terrifying at times, joyful at others. It made me smile more than cringe.

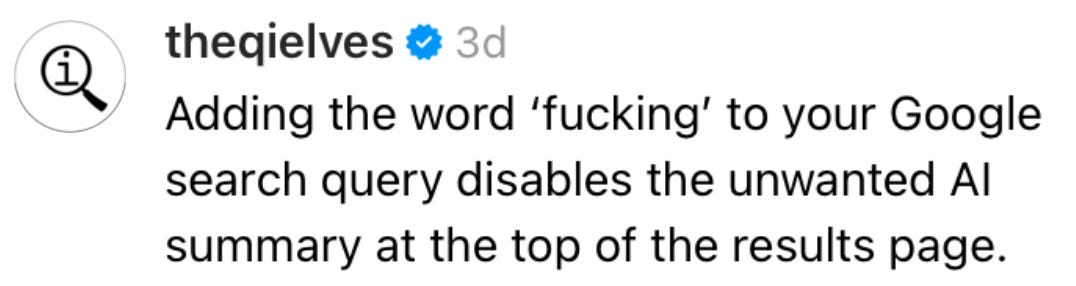

Something blue: This does seem to work. Try it with “Donald Trump immigration policy.” Even if it fails, it’s fun to type “Donald Trump fucking immigration policy.”